A total of five national parliaments have recently been shaken up as a result of the ongoing crisis in the European Union. Most legislation from the EU is voted on in Brussels and presented directly to governments for implemention, thereby bypassing national parliaments. On numerous occasions however, and increasingly so during this period of crisis, the interests of national governments can conflict with the core EU agenda. When the stakes are high and measures must be executed swiftly and decisively, this creates a problem.

Being such a vast and complex project, the unwillingness of one EU member government to agree unquestionably can create a stir in political circles and affect the opinions of other members. When an influential figure casts doubt on a policy, this can severely delay legislation or even spread further doubt on its final execution or success. At times where difficult and important decisions are being taken, particularly when unanimity is required between member states or the policy depends on collective action or sensitive market optimism, the disagreement of one member state, or one individual, is seen as an obstacle that must be overcome. In many such circumstances, the EU has exerted control over national governments when ministerial opinion or democratic forces threaten the success of the centralised plan.

It is difficult to determine exactly how this power is wielded, whether it is the massive weight of political force behind the will of the European elites that simply commands respect, or the much supported European community method, fortified by a myriad of complying institutions and nodding economists, that enthralls elected governments and pushes aside alternative views, or the unimaginable but increasingly plausible explanation of politicians being directly leant on by EU agents. It appears that if anyone with any influence voices opposition to the EU, they are immediately beheaded and replaced with a loyal obedient robot, and any trace of democracy that finds its way into the system is swiftly and decisively extinguished.

|

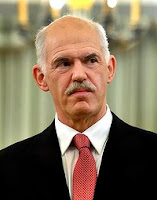

| Papademos resigned after proposing a referendum |

Consider the way that George Papandreou, the Greek socialist prime minister and Euro enthusiast, dared to utter the ‘R’ word in public and cast further doubt on the EU project. He was labelled as ‘incompetent,’ ‘corrupt,’ ‘irrational and dangerous.’ Parliament quickly lost confidence in him and conspired to form a new government, and this was all because he chose to ask the Greek people for their opinion. This week Lucas Papademos was appointed in his place, the former European Central Banker and loyal ‘Frankfurt man,’ who quickly announced that Greece’s future is within the Euro with no mention of the referendum. The project must continue.

|

| Berlusconi resigned after failing to implement credible reforms to Italy's finances |

Think also of how Silvio Berlusconi, the flashy and tenacious Italian prime minister, who had until recently survived every media accusation and political assault in the book, from soliciting underage sex with minors, to links with the mafia, to claims of bribery and fraud, was brought down in days of expressing an anti-EU sentiment. At the recent G20 summit he unwisely asserted that “Italians have been impoverished since the introduction of the euro.” Perhaps this comment alone triggered his eventual demise. Such a statement amongst the Euro elite is understood as the highest form of treachery from a man who no longer cares about the survival of the Euro. Fortunately for the EU, Berlusconi’s colourful past made it easy to swat him aside and his successor will now be Mario Monti, a former European Commissioner and loyal ‘Brussels man.’

From our UK ‘island’ perspective, it seems as if the EU emits some kind of supernatural force which enchants, subordinates and dominates its subjects rendering them incapable of thinking against the established ideology. However for the peoples on the continent, the proximity and history of their relationships must make it much harder to resist this captivation. The established belief, voiced on several occassions by Merkel and Sarkozy, is that “if the Euro fails, Europe fails.” A sense of historical obligation has been built up on the conscience of the European nations, particularly for the Germans, on the belief that to oppose the EU is to opt for instability and war. The fear is that if any opposition to the European project is allowed to gain momentum, the continent will then begin to slide down a slippery slope into poverty, animosity, isolationism and conflict. The Euro is a symbol of the historical commitment to peace and friendship that must be preserved, at any cost.

Papandreou and Berlusconi have not been the only victims of EU domination. Bertie Ahern, the Irish prime minister who won three successive elections as the leader of Fianna Fáil (a centrist party), resigned in 2008 amid fears that allegations about his personal finances would affect the Republic of Ireland’s referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. Despite adamantly denying any wrongdoing, fears still remained that the public could vote no to spite Ahern, thereby adding an element of sleaze into the EU ratification process, the last thing that the EU elites wanted. He was replaced by the deputy prime minister and finance minister, and pro-Euro, Brian Cowen. Despite the prime minister’s yes campaign the Irish voted no to reject the Lisbon treaty, a great victory for democracy, but Cowen returned to Brussels hat in hand and sided with the European Union against his own people to agree a few alterations to the treaty and usher in a second referendum. The second vote passed and the Lisbon Treaty was ratified.

Cowen‘s term coincided with the financial crisis in the wake of the credit crunch of 2007 and the beginnings of the European debt crisis. With the country’s finances quickly deteriorating, Ireland was forced to accept a bailout from the EU and the IMF in addition to a stand-alone loan from the UK, widely seen throughout the country as a national humiliation. Fianna Fáil lists among its primary aims the commitment “to maintain the status of Ireland as a sovereign State,” but Cowen had surrendered the country’s ability to determine its own destiny to the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF.

Brian Cowen showed himself to be a good loyal ‘Brussels man.’ The ideals of his Republican party were left in tatters, Irish taxpayers had been saddled with the burden of rescuing the banking system, and Ireland now faces years of austerity and hard times, but the continuation of the European project was safely secured. Combined with allegations over secretive talks with the Chairman of Anglo-Irish Bank, Cowen quickly came under pressure to step down. The Green Party abandoned the existing coalition stripping Cowen of a majority in Parliament. The government collapsed and Fianna Fail was swept from power in the subsequent general election to be replaced by Fine Gael (centre right) in coalition with the Labour Party (centre left). Unfortunately for the people in Ireland, neither party presents a real alternative to the status quo.

The EU has already demonstrated on many occasions its power to change governments, and open up opportunities for others to assume power. Where opposition to the EU is voiced in government, those in power can encounter legitimate barriers to fulfilling the requests of their EU overlords, whether it be democracy rearing its head at an inconvenient moment or the promises made to hold together a coalition government. However, even if this leads to the deposition of a leader or ruling party, it makes little difference to the course of events as the replacement government is unable to change the preordained European agenda.

Consider prime minister Iveta Radicova of Slovakia, who lost a confidence vote last month tied to the ratification of an expansion to the European stability fund (the EFSF), to which all Euro-zone countries would contribute. In order to secure support for the plan, Radicova sought support from opposition in exchange for early elections set for March of next year. The EFSF expansion was passed on a second vote and the ‘Slovakia problem’ was solved. A small country such as Slovakia has limited defences against the EU’s bullying and it is unclear as to what end the resulting political upheaval will lead.

Think also of Jose Socrates, the former Portuguese socialist prime minister, who resigned after failing to implement spending cuts and tax hikes in order to bring down the fiscal deficit so as to avoid a bailout. Austerity measures were met with huge resistance in Portugal and thousands took to the streets in protest. The government tried to implement the Stability and Growth Pact without consulting Parliament or the President. (This is the set of requirements for monetary union such as a low debt/GDP ratio and a low annual budget deficit, which so many of the Euro-zone countries have long since surpassed.) Socrates previously said that if the austerity measures fell through he would be unable to govern. All other parties voted against the measure and Socrates stepped down in March 2011. The president called for early elections for June and a conservative government took office led by Pedro Passos Coelho of the Social Democrats and the Peoples Party in coalition. Again, it is yet unclear if Portugal’s change in government will give the people any more of a say in their future. Socrates was forced to ask for a bailout back in April before stepping down and austerity protests still continue.

As the Euro crisis unfolds, key decisions and next steps for the future of the single currency are increasingly being decided by a small group of elites, with the opinion of national governments being consulted only after the decisions have been made, if at all. This ‘inner circle’ consists of Merkel, Sarkozy, Juncker, the prime minister of Luxembourg and chairman of the Euro group, Lagarde, the head of the IMF, Draghi, the Italian president of the ECB, Rehn, the Finnish EU finance commissioner, Van Rompuy and Barroso. Only three of the ‘inner eight’ were elected in their respective countries; the other five are appointed bureaucrats.

From our UK ‘island’ perspective, it seems as if the EU emits some kind of supernatural force which enchants, subordinates and dominates its subjects rendering them incapable of thinking against the established ideology. However for the peoples on the continent, the proximity and history of their relationships must make it much harder to resist this captivation. The established belief, voiced on several occassions by Merkel and Sarkozy, is that “if the Euro fails, Europe fails.” A sense of historical obligation has been built up on the conscience of the European nations, particularly for the Germans, on the belief that to oppose the EU is to opt for instability and war. The fear is that if any opposition to the European project is allowed to gain momentum, the continent will then begin to slide down a slippery slope into poverty, animosity, isolationism and conflict. The Euro is a symbol of the historical commitment to peace and friendship that must be preserved, at any cost.

Papandreou and Berlusconi have not been the only victims of EU domination. Bertie Ahern, the Irish prime minister who won three successive elections as the leader of Fianna Fáil (a centrist party), resigned in 2008 amid fears that allegations about his personal finances would affect the Republic of Ireland’s referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. Despite adamantly denying any wrongdoing, fears still remained that the public could vote no to spite Ahern, thereby adding an element of sleaze into the EU ratification process, the last thing that the EU elites wanted. He was replaced by the deputy prime minister and finance minister, and pro-Euro, Brian Cowen. Despite the prime minister’s yes campaign the Irish voted no to reject the Lisbon treaty, a great victory for democracy, but Cowen returned to Brussels hat in hand and sided with the European Union against his own people to agree a few alterations to the treaty and usher in a second referendum. The second vote passed and the Lisbon Treaty was ratified.

Cowen‘s term coincided with the financial crisis in the wake of the credit crunch of 2007 and the beginnings of the European debt crisis. With the country’s finances quickly deteriorating, Ireland was forced to accept a bailout from the EU and the IMF in addition to a stand-alone loan from the UK, widely seen throughout the country as a national humiliation. Fianna Fáil lists among its primary aims the commitment “to maintain the status of Ireland as a sovereign State,” but Cowen had surrendered the country’s ability to determine its own destiny to the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF.

|

| Cowen resigned after disgracing the most popular political party in Ireland |

The EU has already demonstrated on many occasions its power to change governments, and open up opportunities for others to assume power. Where opposition to the EU is voiced in government, those in power can encounter legitimate barriers to fulfilling the requests of their EU overlords, whether it be democracy rearing its head at an inconvenient moment or the promises made to hold together a coalition government. However, even if this leads to the deposition of a leader or ruling party, it makes little difference to the course of events as the replacement government is unable to change the preordained European agenda.

Consider prime minister Iveta Radicova of Slovakia, who lost a confidence vote last month tied to the ratification of an expansion to the European stability fund (the EFSF), to which all Euro-zone countries would contribute. In order to secure support for the plan, Radicova sought support from opposition in exchange for early elections set for March of next year. The EFSF expansion was passed on a second vote and the ‘Slovakia problem’ was solved. A small country such as Slovakia has limited defences against the EU’s bullying and it is unclear as to what end the resulting political upheaval will lead.

|

| Socrates resigned after failing to pass austerity measures without seeking EU assistance |

As the Euro crisis unfolds, key decisions and next steps for the future of the single currency are increasingly being decided by a small group of elites, with the opinion of national governments being consulted only after the decisions have been made, if at all. This ‘inner circle’ consists of Merkel, Sarkozy, Juncker, the prime minister of Luxembourg and chairman of the Euro group, Lagarde, the head of the IMF, Draghi, the Italian president of the ECB, Rehn, the Finnish EU finance commissioner, Van Rompuy and Barroso. Only three of the ‘inner eight’ were elected in their respective countries; the other five are appointed bureaucrats.

|

| The 'inner eight', clockwise from top left, Jean-Claude Juncker, Nikolas Sarkozy, Angela Merkel, Mario Draghi, Christine Lagarde, Herman Van Rompuy, José Barroso, Olli Rehn |

As the inner eight sit in their bunker and discuss the fate of the Euro, democracy must be a niggling worry in the back of their minds. So far, all is not yet lost, and the Euro is still in one piece, so to speak. Trouble-makers such as Berlusconi and Papandreou have been eradicated and despite the loss of a few loyal subjects such as Brian Cowen, the new governments should not start up too much fuss; they know better.

The survival of the Euro is what everyone should hope for, but must this come at the price of national democracy? The increasingly centralised decision making from the Brussels-Frankfurt inner circle and the demands put on national governments to act obediently is putting a huge strain on the democratic legitimacy of the whole project. The protesters that we see in Athens and Lisbon etc. will only relent when decisions about their country’s future are being taken by the people they elect, or by themselves directly. Failure to take the democratic route will lead to revolt, be it from Greeks who believe that they are suffering unnecessarily, or Germans who believe that they are paying unnecessarily. If austerity is the only option for the south, and taxpayer borne bailouts are the only option for the north, then the national governments need to be honest to their people and take these decisions autonomously in the best interests of the country. Let us hope that European leaders recognise that if the break up of the Euro is in the best long term interests of the continent then it should be seriously considered and planned as soon as possible. Even the best of us make mistakes, and a break up of a currency does not need to lead to the break up of our friendship and cooperation as Europeans.

Actually Ahern was proven to be corrupt, by a legal process that has cost the Irish people multi millions and taken years to complete.

ReplyDeleteIt appears his final defence of having won unexplained cash lodgements on horse races to accounts he denied having to start with were considered to be unacceptable by the tribunal.

Yes Ahern should be in jail or at the very least facing court proceedings.

Cowen was proven to be incompetent, as a leader of Government who was more interested in saving his political party than concentrating on the affairs of State.

That said Cowen's incompetance could very easily have been used by the E.U. to ensure Ireland's interests were not truly represented in the banking crisis.

The present administration led by Enda Kenny are a bunch of E.U. yes men, in fact one of his Government Minister went on radio to debate for a yes vote in the upcoming referendum, it transpired during the debate that the Minister had not read the treaty.